Organizing Care Around People and Places: The People’s Healthcare Act and Integrated Care Delivery Systems

At our firm, we regularly keep an eye on public sector developments for our clients. In Ontario, the healthcare landscape is changing. On February 26th, the government introduced Bill 74, The People’s Health Care Act, 2019. On March 8th, it announced a new board of directors for the “superagency” described in the bill, Ontario Health.[1] This new legislation speaks of “integrated care delivery systems”, one of many emerging models of care organized around people and places. Sometimes called integrated care systems or population health systems, these new models represent a change to how healthcare is structured and delivered, focusing on defined populations and health outcomes, rather than organizations and services.

In this note, we:

- Briefly orient healthcare decision makers to the different terms and summarize key features of these models in the United States and United Kingdom

- Suggest areas of focus for Ontario’s healthcare system planners, health service providers, and hospitals in particular, to start their transition to these new models of care

Dramatic Changes

Ontario’s government is not making minor adjustments when it comes to the healthcare system – dramatic changes are in progress.

Under the new legislation, Ontario Health is expected to take over system planning and a variety of provincial program roles and responsibilities from many existing entities. And when it comes to population health and integrated care, it is clear that health service providers will be asked to increase collaboration and integration of services through the new integrated care delivery systems, currently called “Ontario Health Teams”. The legislation speaks of these systems as a person, entity, or group of people or entities that have “…the ability to deliver, in an integrated and coordinated manner, at least three of the following types of services:

- hospital services,

- primary care services

- mental health or addictions services,

- home care or community services,

- long-term care home services,

- palliative care services,

- any other prescribed healthcare service or non-health service that supports the provision of health care services…”[2]

While the last clause provides some flexibility, there is a clear expectation that health care providers need to work together to provide integrated care.

Plan and Know What You Can Do

For health service providers, it is important to:

Start Planning Early – Several organizations have already started planning for the new population health/integrated healthcare environment. While those that move first will encounter implementation challenges first, they will also learn faster, attract staff that can help them innovate, and likely garner more resources over the long term.

Know What You Can Do – While significant structural changes are underway, there is still substantial work that can be accomplished in the meantime. Activities such as planning, scoping, identifying like-minded partners, and analyzing populations and approaches can proceed while policy details are being finalized.

A Quick Tour: Population Health Systems, Integrated Care Models and More

When people speak about population health and integrated care, the conversation often remains ambiguous. And as it gets more specific, one often finds oneself saying, “Sorry, what do you mean exactly?” So rather than pile on the terms with needless consulting jargon, we will take you on a quick tour of the literature we have found helpful in thinking about population health and integrated care systems so that you can press on.

What is a Population Health System?

In a population health system, many providers work as a single organization to take accountability for the health needs and well-being of a defined population, by integrating services across multiple domains such as healthcare, prevention, social care and welfare.

Population health systems do more than just treat people once they are ill – they also work to proactively maintain and improve people’s heath through community-based care, education and self-management support.

Apart from being good practice and addressing the links between social determinants of health and health itself, they also work to reduce demand for expensive care settings, like hospitals and long-term care homes.

In 2015, The King’s Fund published a helpful overview of population health systems that distinguishes them from integrated care models.[3] It includes several brief case studies including Kaiser Permanente as well as others from Sweden, New Zealand, and Germany. The key distinction they make is that:

- Population health systems are focused on “[i]mproving health across whole populations, including the distribution of health outcomes”, while

- Integrated care models are focused on “…[c]o-ordination of care services for defined groups of people (e.g., older people and those with complex needs)”.[4]

Ontario Versus the US and UK

To date, Ontario has pursued a number of initiatives that skirted the line between these two concepts, including redesigning service pathways for specific populations (e.g., Health Links, Integrated Care Collaboratives) and value-based payment models (e.g., Quality-Based Procedures, bundled funding models). But the United States – through Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) – and the United Kingdom – through Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) – are further down the path toward population health systems.

While structure, scope and approach vary among ACO models (there are now over 1,000 active ACOs in the United States[5]), they share common features and approaches. Successful ACOs tend to be well-coordinated groups of doctors, hospitals, and other care providers who coordinate high-quality care for a defined population across the care continuum. This includes the basic clinical functions of:

- Coordinating clinical service delivery among all participating providers

- Facilitating the delivery of more effective and efficient care through increased access, population management, care management and care self-management education

- Translating patient clinical and service use data to promote more effective and proactive care at a population-level6]

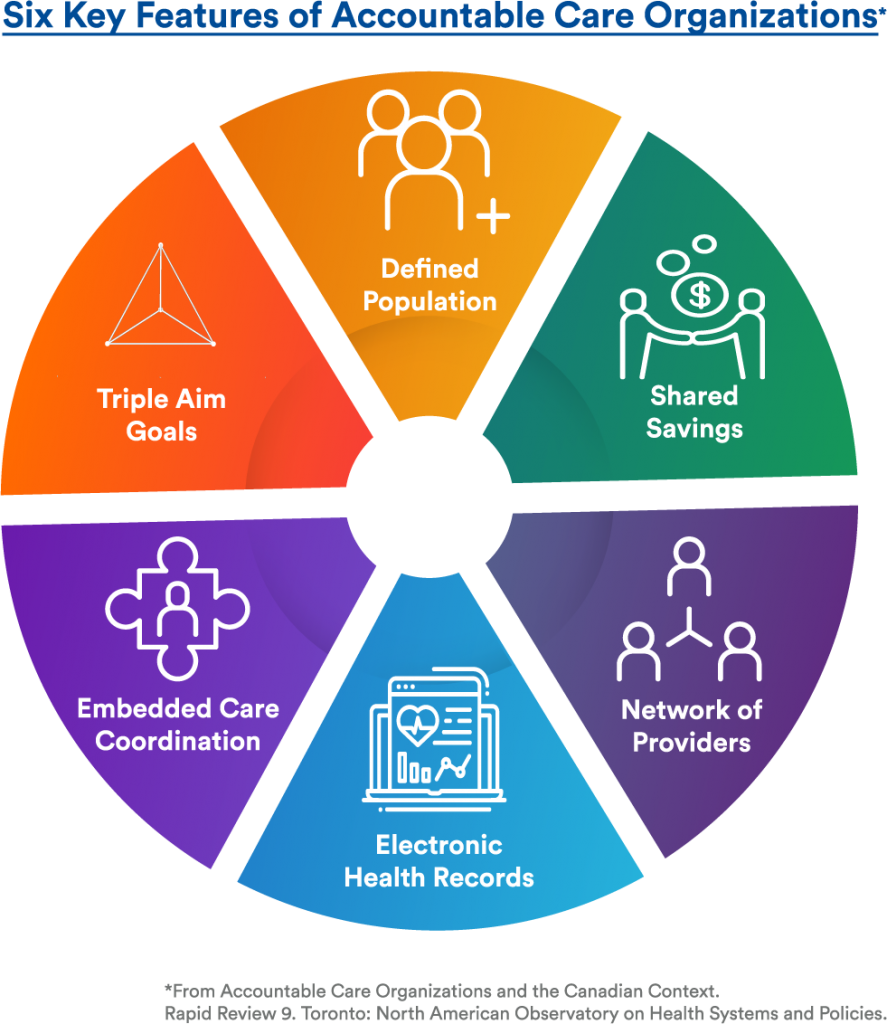

Six key features of ACOs have been identified by a group of prominent Canadian researchers, outlined in Figure 1 below: defined populations, triple aim (or quadruple aim) goals, embedded care coordination, electronic health records, networks of providers, and shared savings.[7] Importantly, they note that while many of these features have been present in recent new models of care piloted in various jurisdictions in Canada, no single model has included all features of an ACO model to date.[8]

Figure 1: Six Key Features of ACOs Identified in the North American Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Rapid Review[9]

The United Kingdom’s ICSs include and expand upon the ACO scope, with the intent of collaborating more routinely with local authorities and social care providers to address social determinants of health.[10] While it is early days for ICSs, who have been focused on establishing governance[11], they are likely to replicate in some manner the six key features of ACOs.

What is Applicable in Ontario?

If you are a health system planner or hospital executive, there are certain organizations often held up as models to emulate, like Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Health, or Geisinger Health System. At Optimus SBR, when they do come up, we caution our clients that it is often forgotten they operate in different environments: different federal/state responsibilities, different contractual relationships with physicians, different funders, and different patients. Local context needs to be considered when adapting these models to Ontario.

What You Can Do

Health service providers can start creating population health systems or integrated care models today, and these efforts will be relevant for the most part regardless of what changes occur in Ontario now or in the future. These models are about working in partnership with others to improve the patient experience and deliver care with a population and outcome focus.

To get started, we recommend hospitals and health service providers focus on the items below.

Identify the right role for your organization and get started:

- What role is right for your organization? At present, expectations are that there will be 30-50 Ontario Health Teams in Ontario once they are fully rolled out. Health system planners and particularly health service provider and hospital leaders need to examine their local health system and context, and consider their own organizational capabilities and strengths alongside those of potential partners. There is no set role for providers of a certain type in these models, so planning is needed to identify the right role for your organization and potential partners that are a good fit with local needs. What drives population health where you are? What are you good at? What are you not so good at? Who has certain strengths that you lack?

- Then get started. As you do so, we recommend not getting overly caught up in governance. This is different from how most providers typically plan and implement today, and in the past drawn out governance conversations have limited the system’s ability to achieve timely change. Patients do not have time to wait – the way you organize and deliver care needs to change today.

Build a network of partners and providers, likely starting with primary care:

- While formal Ontario Health Team partnerships may need to wait, you can start talking to potential partners and establishing effective working relationships. You can learn more about patient populations and how you can collectively serve them.

- In particular, a strong and tactical partnership with local primary care is often crucial. Primary care is the cornerstone of integrated, population-based care models. In the short term, you may need to identify a primary care coalition of the willing, then broaden it over the next few years. The main idea is to get going, and expand governance and partnerships as you iterate and grow your local model.

Segment populations and redesign approaches across care settings:

- The prospect of being held genuinely accountable for population health will likely focus people’s minds. Consequently, you will want to understand your local populations better, segmenting and stratifying and then designing approaches that work with you and your partners in your local context.

Learn more – Decision Time on Ontario Health Teams: The Changing Ontario Health Care Landscape – Part 2

Optimus SBR’s Healthcare Practice

Optimus SBR is an implementation-focused firm that specializes in turning policy into action. Our team has significant experience working with major healthcare stakeholders, from the MOHLTC, large hospitals, LHINs, home and community care, and community health service providers. We partner to create new models of care, facilitate decision making, and develop proposals for government approval. With our real world healthcare integration experience, we can get you delivering on the outcomes you need to deliver today.

If you have found this helpful, give us a call, or send us a note.

Brad Ferguson, SVP, Industries and Government Practice

Brad.Ferguson@optimusssbr.com

416.649.9184

David Lynch, Principal

David.Lynch@optimussbr.com

Jason Huehn, Manager

Jason.Huehn@optimussbr.com

References

[1]Government of Ontario (2019). Backgrounder: Ontario Health Board of Directors. March 8, 2019. [online: web] URL: https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2019/03/ontario-health-board-of-directors.html.

[2] Bill 74, The People’s Health Care Act, 2019, 1st Sess, 42nd Parliament, Ontario, 2019, s.29(2)(a). Italics added. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis?category=long-read

[3] Alderwick, Hugh, Chris Ham, and David Buck (2015). Population Health Systems: Going Beyond Integrated Care. London: The King’s Fund. [online: web] URL: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis?category=long-read

[4] Ibid.

[5] Muhlestein, David, Robert Saunders, Robert Richards, and Mark McLennan (2018). “Recent Progress In The Value Journey: Growth Of ACOs and Value-Based Payment Models In 2018.” Health Affairs Blog, August 14, 2018. [online: web] URL: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180810.481968/full/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Peckham, A., D. Rudoler, D. Bhatia, S. Fakim, S. Allin, and G. Marchildon (2018). Accountable Care Organizations and the Canadian Context. Rapid Review 9. Toronto: North American Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. [Online: web] URL: https://www.utoronto.ca/

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Charles, Anna, Lillie Wenzel, Matthew Kershaw, Chris Ham, and Nicola Walsh (2018). A Year of Integrated Health Systems: Reviewing the Journey So Far. London: The King’s Fund. [online: web] URL: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/year-integrated-care-systems

[11] Ibid.

Industry Insights

Service Insights

Case Studies

Company News